Newark Chapter 3: Phenomenal Early Charter Schools Redefine the Possible

From the very first day that charter schools began to operate in Newark, it was clear to many that a completely new way of providing public education had arrived.

In her book about the early history of the charter school movement in the United States …

… long-time New Jersey educator Sarah Tantillo described the impact of witnessing the community meeting that happened on North Star Charter School Academy’s first day.

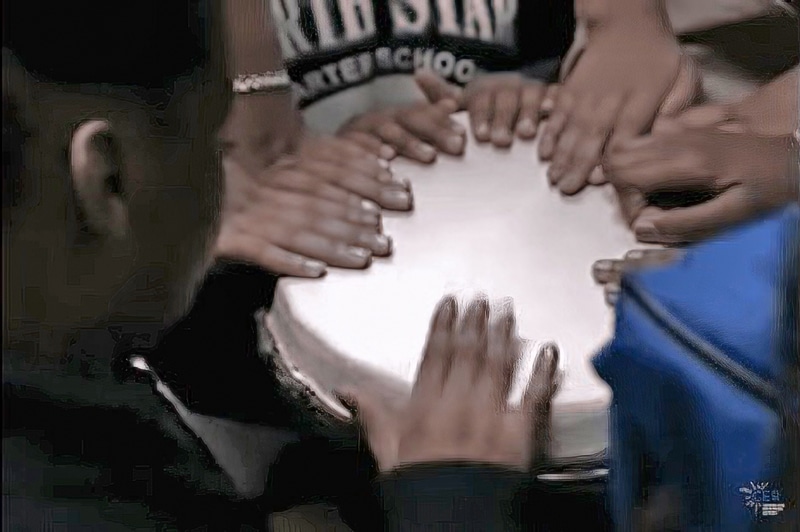

One by one, each student walked up, hit the drum, and returned to the circle. As we stood there, the only sound was the loud slam of each child’s fist on the drum. PWOW. PWOW. PWOW …

I felt my heart being pulled in. As I watched and listened and fought back tears, all I could think was, if this was the very FIRST day of school is like, what is TOMORROW going to be like?

What Tantillo described was a morning meeting ritual …

… involving student drumming …

… and community affirmation, including a shared stressing of the importance of all students receiving a great public education.

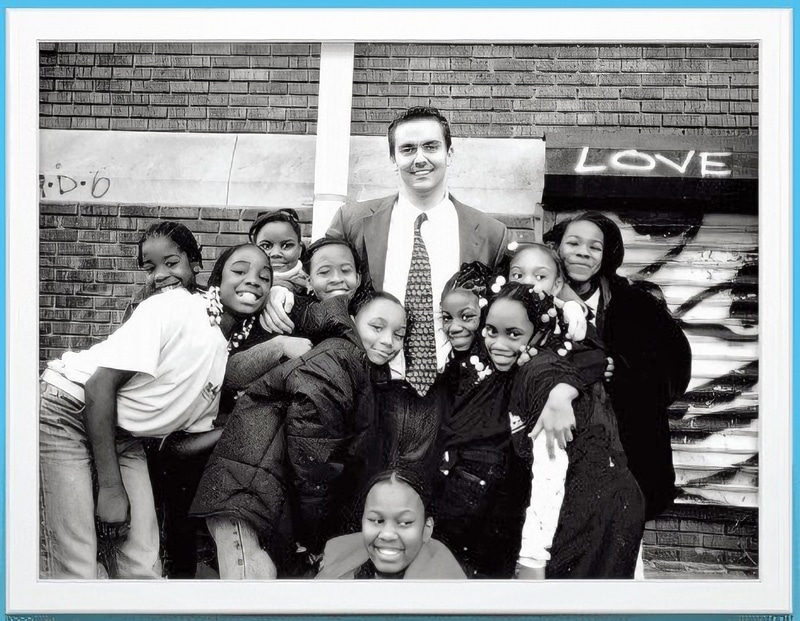

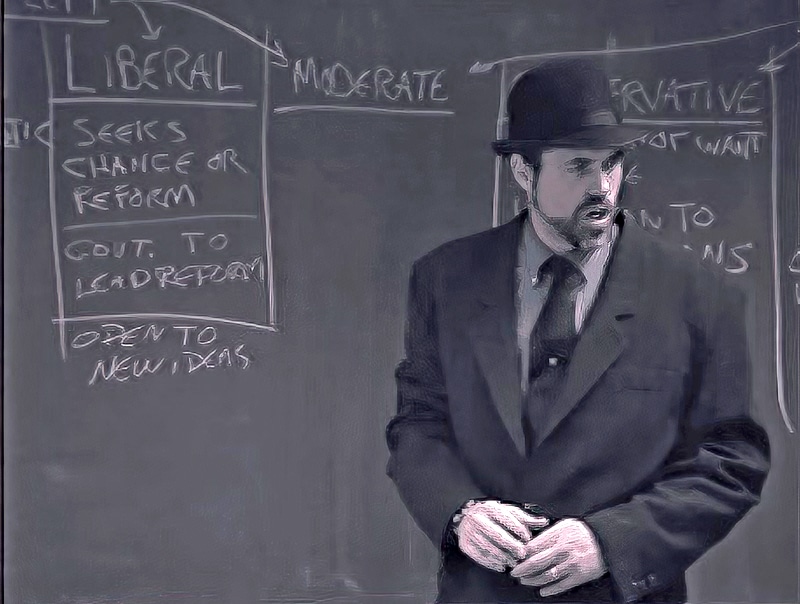

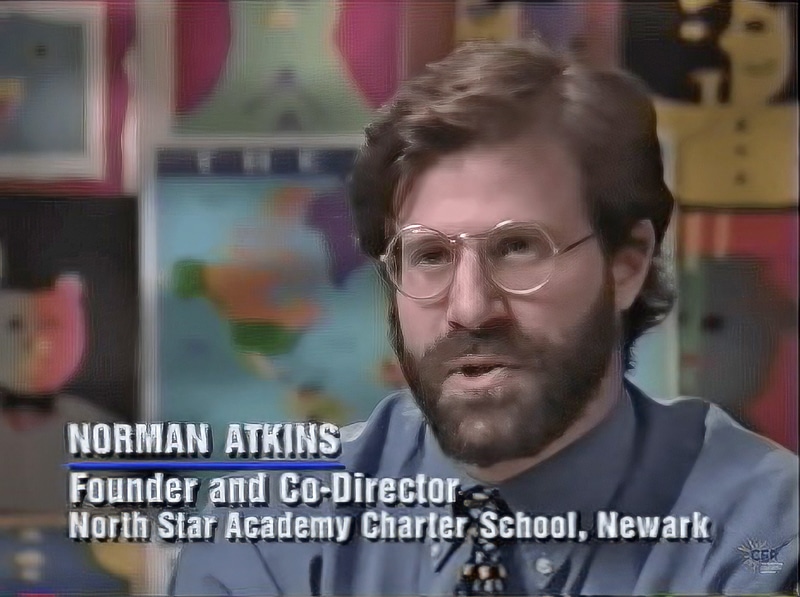

Upon observing James Verrilli teach in the days before chartering, Norman Atkins had come to the opinion that Verrilli was “the greatest teacher he had ever seen.” North Star Charter School Academy became the full expression of Verrilli’s vision for how great teaching could be manifest throughout an entire school. Not only, did Verrilli help to create compelling morning meetings and other rituals that built a strong school culture, but he brought imagination and passion to the classroom, often dressing up to impersonate historical figures in order to make history’s lessons more alive to his students.

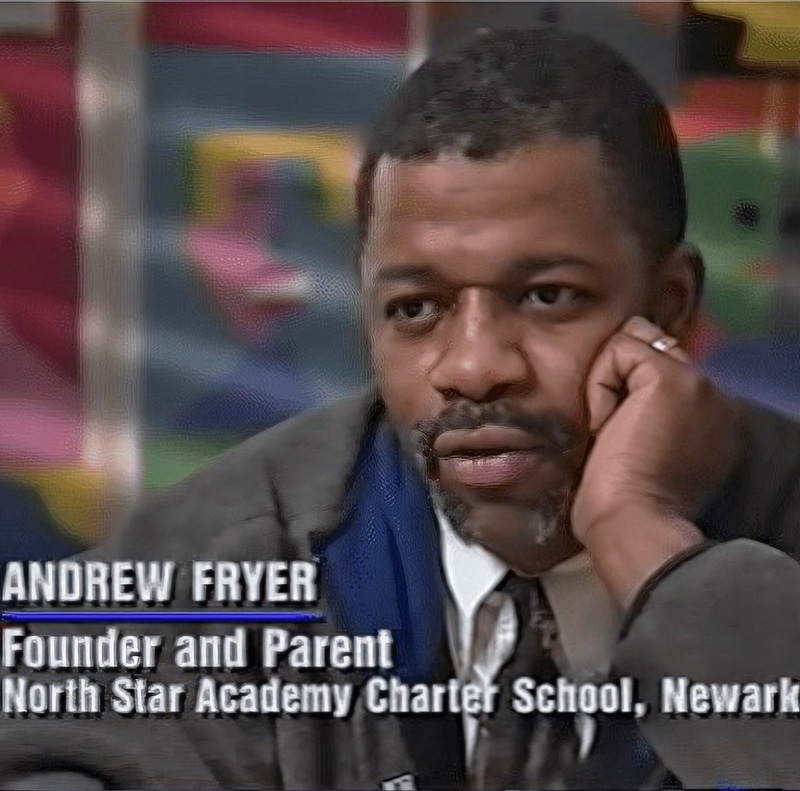

He and Atkins also recruited an extraordinary group of school founders from the local community, including Andrew Fryer, who served as a founding board member …

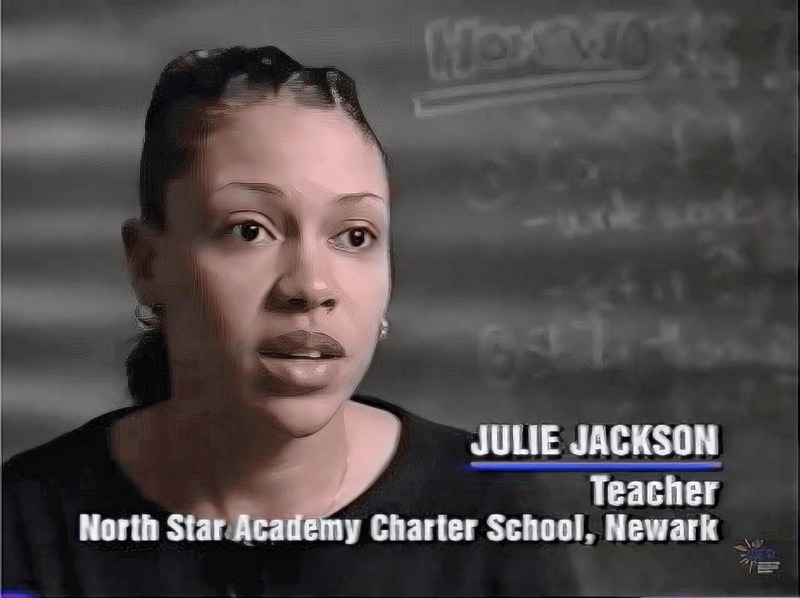

… and Julie Jackson, who served as a founding teacher.

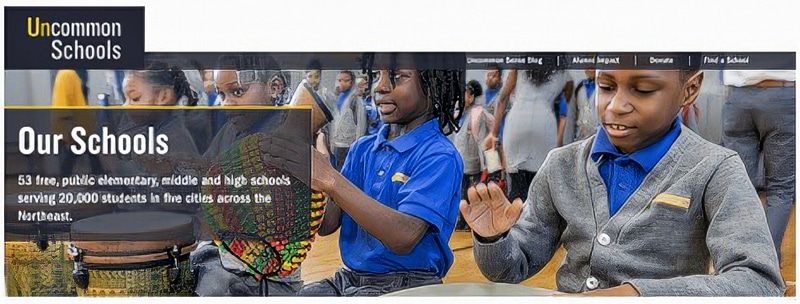

That’s the same Julie Jackson who has gone on a quarter century later to be the Co-CEO of Uncommon Schools …

… the charter management organization initiated in part by North Star, which currently operates 53 schools in Newark, New York and Massachusetts …

… and where students are still playing the drums at morning meetings to this very day.

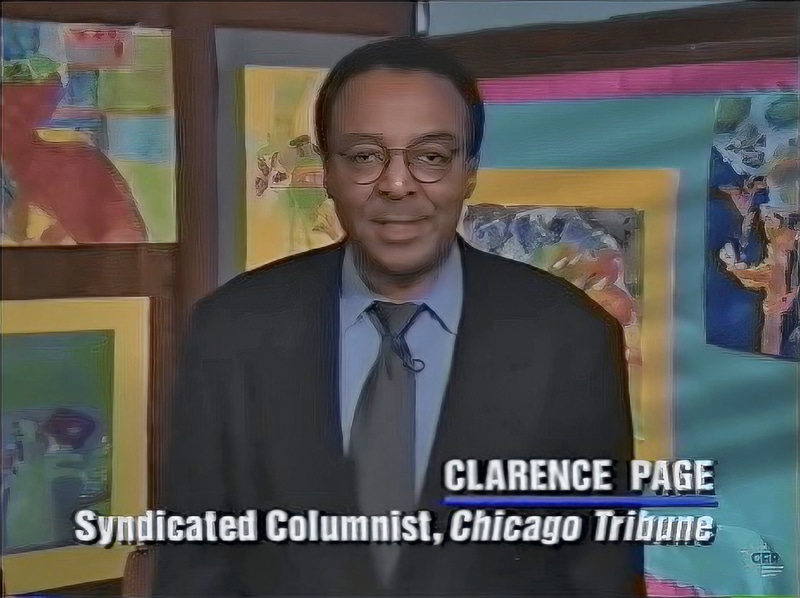

Within a few years of opening, North Star Academy Charter School was being recognized as one of the strongest charter schools in the country. When noted columnist Clarence Page …

… made a video essay in 2000 about the emergence of the nascent charter school movement across the United States …

… the very first school he profiled as an example of one that “works” …

… was North Star Academy, a school in the heart of Newark’s Central Ward.

By 2004 when North Star’s first group of students completed high school, 100% of graduates matriculated to college, something that was simply unprecedented for a graduating senior class in the City of Newark.

But for all the success that North Star had, it was by no means the only school to greatly exceed expectations in the early years of Newark’s chartering movement.

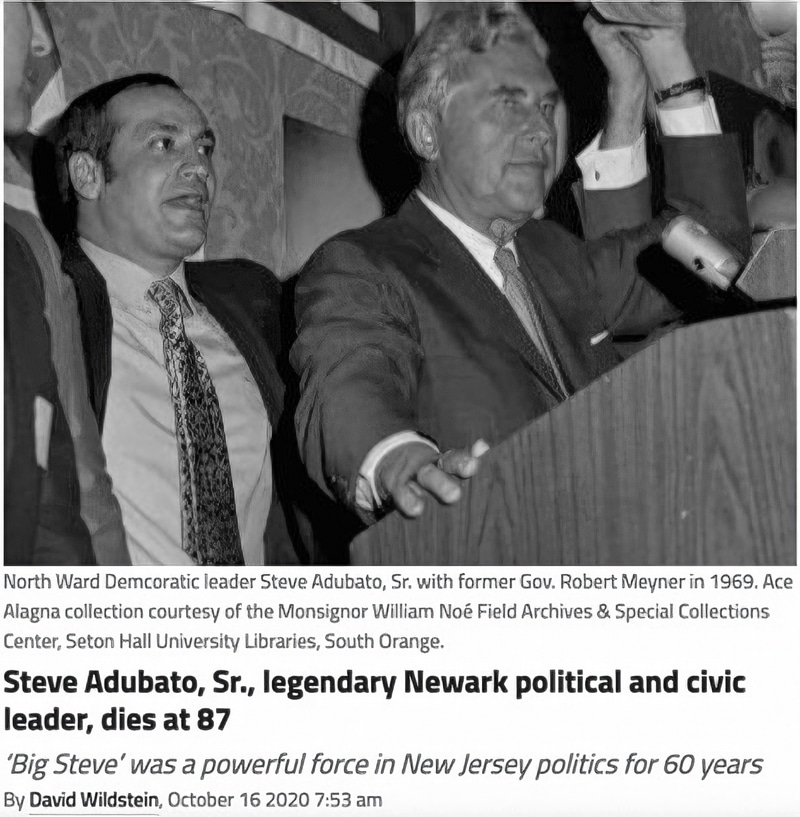

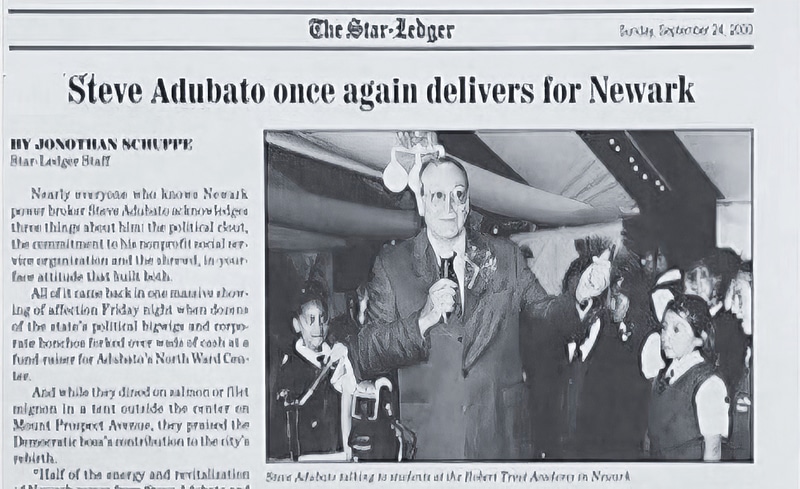

Robert Treat Academy also opened in the summer of 1997, the brainchild of a legendary figure …

… Stephen Adubato, a lifelong resident of Newark’s North Ward who had spent many years teaching and serving on the executive board of the Newark Teachers Union. Early in his career, he had become an influential leader within the Democratic Party, supporting the campaigns of many prominent New Jersey Democrats going back to the 1960s, as an obituary tribute recently recounted.

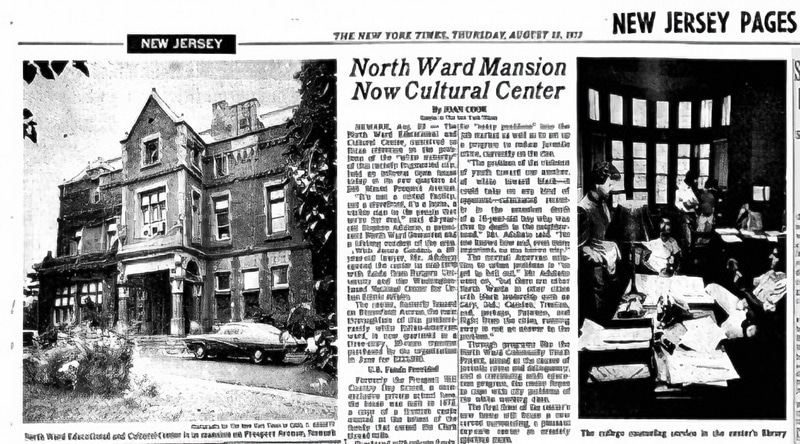

In the early 70s, Adubato partnered with fellow Newark teacher Adrianne Davis …

… to found the North Ward Center …

… a social service agency operating a range of programs in the community including pre-school, college advising, adult training, and supports for seniors.

When New Jersey’s charter school law passed, Adubato and Davis recognized that a natural next step for the Center would be to open a charter school for the families of the North Ward. As Adubato described it in 2002, the idea was to found a school that was freed up from the constraints holding back other public schools to create higher expectations that challenged both kids and adults.

The biggest crime in urban education is our kids are not challenged. The more our kids are challenged, the more they look for challenges …

We are not buried under bureaucracy. We can stick to the simple task of educating children. We have much higher expectations. Our school opens at 7:30 in the morning. Closes at 5:30 at night. It’s open 11 months a year, and now we’re starting Saturday classes.

First: Challenge. Create a situation where kids are challenged.

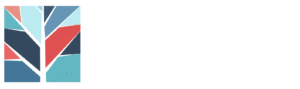

Like North Star, Robert Treat Academy invested deeply in culture-building exercises, creating its own morning meeting rituals …

… and it stressed the importance of maintaining small class sizes where students would have hands-on learning opportunities across the curriculum.

Within just a few years of opening, Robert Treat Academy’s higher expectations began drawing widespread attention both in the local press …

… and nationally.

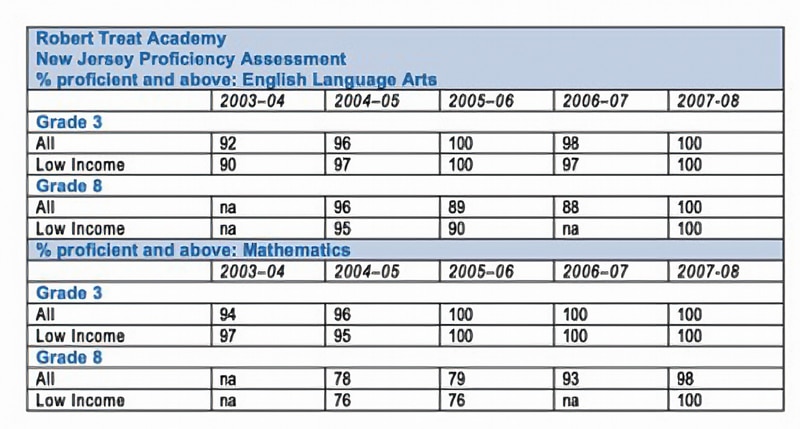

Soon results on state-mandated tests showed that unprecedented levels of academic achievement were being generated by the school.

It resulted in Robert Treat generating a headline that was essentially unheard of for a city whose public education system was otherwise known to be in crisis.

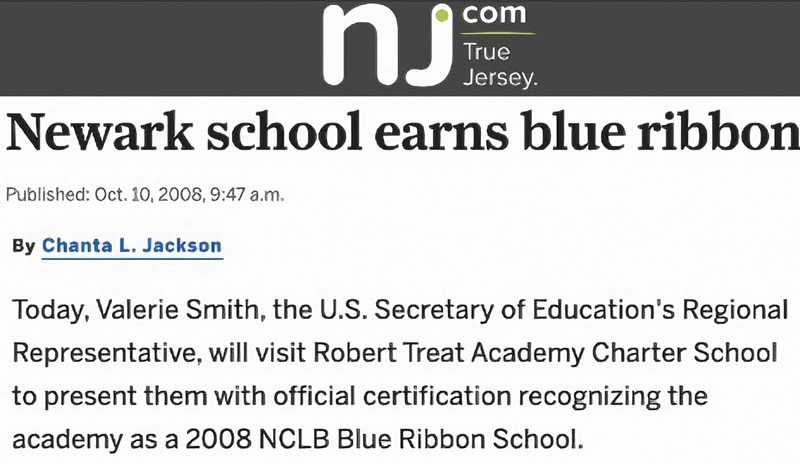

The City of Newark had a National Blue Ribbon School.

And soon thereafter, Robert Treat generated another unusual headline:

Even more high-quality public education options were coming to the city’s Central Ward.

Soon other charter schools began following in the trail blazed by North Star and Robert Treat.

Both Marion P. Thomas Charter School, which opened in 1999, and The Gray Charter School, which opened in 2000, continue to thrive as successful schools nearly a quarter century later. In fact, in 2019, the State of New Jersey identified Gray to be the highest performing public school in all of Newark.

Surely, though, not every charter school that opened in Newark in the early years of chartering proved successful over the long term. In 2018, a school that had opened in 2001, Lady Liberty Charter School, was closed by the State due to poor academic performance.

But the overall story in the early years of chartering in Newark was a steady drumbeat of highly successful schools opening which offered a quality of education, unlike anything the city had seen in decades. It was a drumbeat that beckoned more long-time Newarkers to get involved.

In 2002, Team Academy opened in Newark’s South Ward serving 80 5th-grade students. Ryan Hill, who had previously worked as a teacher in New York City, was the principal.

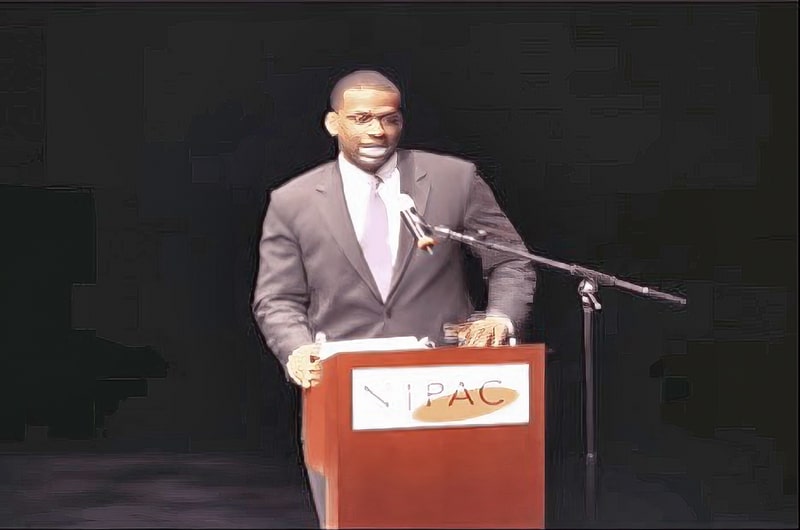

From his earliest days working to start the school, Ryan had partnered with Shavar Jeffries, a native of Newark whose grandmother had raised him and had been a public school teacher in the city. After getting his undergraduate degree from Duke and a law degree from Columbia, Jeffries was looking for opportunities to put his civil rights and legal background to work on education issues in his own hometown. So, when Hill asked Jeffries to serve as Team Academy’s first board chair it was natural for Jeffries to agree.

I gladly accepted, and I accepted because I was certain that our children would accomplish greatness if we expected it of them. If we demanded greatness of them and of ourselves. So I had no choice but to accept. At that point, we didn’t have a board. We didn’t have a building. We didn’t have teachers. We didn’t have administrators or a development staff. We didn’t even have students. All we had was a vision. Ultimately, I realized in retrospect, that vision is all we really needed. And that vision was one in which we had an uncompromising, non-negotiable belief in the capacity that every child can and will accomplish everything that you expect of that child.

It was a beginning for an organization that was as auspicious as the beginning of the entire charter school movement was experiencing in Newark.

Two decades later, Team Academy had grown to become KIPP New Jersey serving nearly 8,000 students in 18 schools in Newark and Camden …

… and Shavar Jeffries had become the CEO of KIPP Foundation supporting a network of 280 schools nationwide with 175,000 students and alumni.

Without a doubt, the success of Newark’s early charter schools was beginning to redefine the possible.