Newark Chapter 1: The Tragedy that Preceded Chartering

In January of 1975, Harpers Magazine ran an edition …

… containing an article portraying Newark, New Jersey as “The Worst American City.” The article found that in 19 of 24 categories, Newark ranked among the five worst cities in the country. Among the problems cited in the article was the well-known fact that Newark’s schools were among the most challenged of any in the nation.

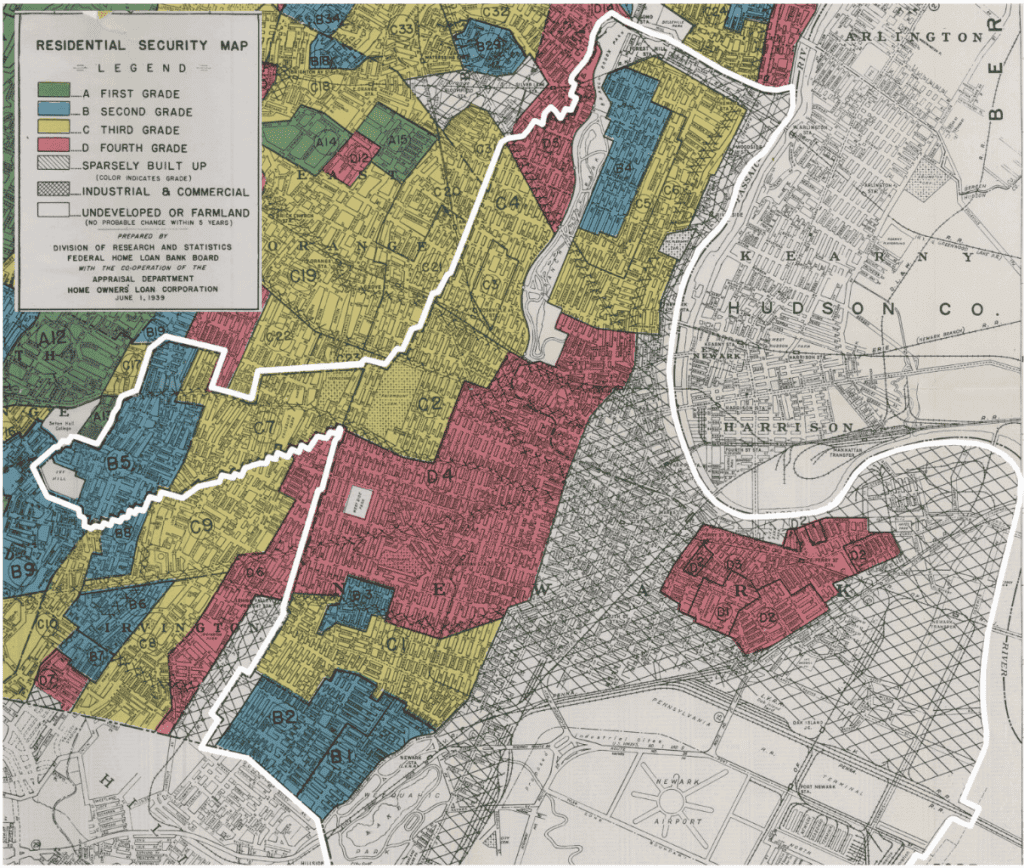

It hadn’t always been this way. Indeed, Newark had among the earliest publicly supported schools in the United States, with public requisition of funds in support of public education going back to the 1760s. The city’s investment in public education was extensive through the 1800s as Newark grew to be the 14th largest city in the United States, housing a manufacturing base in the early 20th century that provided for a robust local economy. As the great migration of Black people to urban areas in the north accelerated through the Second World War, Newark saw its population continue to rise. The increase in Black residents coincided with the imposition of redlining housing policies throughout the city …

… and the rise of White flight to surrounding suburbs. Many historians identify the civil disturbances of 1967 …

… to be an important watershed that resulted in an acceleration of white residents leaving the city. That was coupled with many large companies leaving the area as well resulting in a diminished tax base and a depressed local economy.

These broader societal changes had a great impact on Newark’s public schools. Various commissions and studies that occurred after the 1967 rebellion concluded that student educational attainment was at appallingly poor levels. By the early 70s, the Newark Teachers Union had become the collective bargaining unit for the district’s teachers, and for the next two decades, a parade of superintendents reflected the fact that a fundamental instability in executive leadership had gripped the district. Meanwhile, paradoxically, a profound stasis in political leadership had set in. Noted historian Robert Curvin in his highly respected history Inside Newark reported that during this period the mayor, who maintained ostensible control of the city’s schools through his power to name appointees to the board of education, saw the school district, which offered a larger number of jobs and managed a larger amount of funding than any other entity in the city, as a source of patronage and a resource for directing favors to political allies and insiders.

In 1982, Newark voters approved the creation of an elected school board, dislodging control of the schools from the mayor, but that change did little to affect the perception that the school district was failing to serve its community well. In 1988, federal investigators descended upon the school district in response to allegations of widespread corruption. A 1991 report commissioned by the state confirmed that graft and kickbacks were widespread within the system.

That led to some convictions of district leaders.

By that time, Newark Public Schools operated approximately 80 schools serving just fewer than 50,000 students, and calls were growing louder for state intervention. Finally, in the spring of 1993, Education Commissioner Mary Lee Fitzgerald and New Jersey Governor James J. Florio came together to take action.

Their first step was calling for the state to undertake a Comprehensive Compliance Investigation of the district.

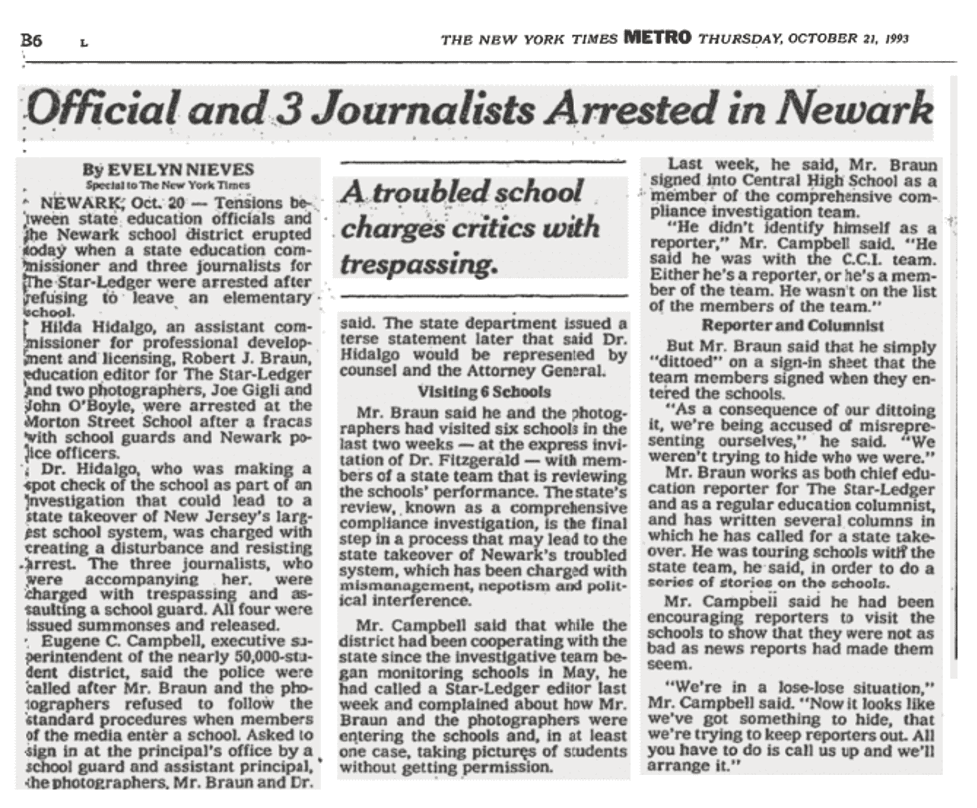

Recognizing the level of threat that the investigation represented, the district’s leadership did all they could to throw roadblocks in its way, going so far as to summon police to arrest a state official and three journalists from the New Jersey Star-Ledger who were attempting to document a spot check being undertaken as part of the investigation.

Hilda Hidalgo, an assistant commissioner for professional development and licensing, Robert J. Braun, education editor for The Star-Ledger and two photographers, Joe Gigli and John O’Boyle, were arrested at the Morton Street School after a fracas with school guards and Newark police officers.

Dr. Hidalgo, who was making a spot check of the school as part of an investigation that could lead to a state takeover of New Jersey’s largest school system, was charged with creating a disturbance and resisting arrest. The three journalists, who were accompanying her, were charged with trespassing and assaulting a school guard. All four were issued summonses and were released.

District leadership also refused to allow its staff to be interviewed for the investigation until a court compelled them to do so.

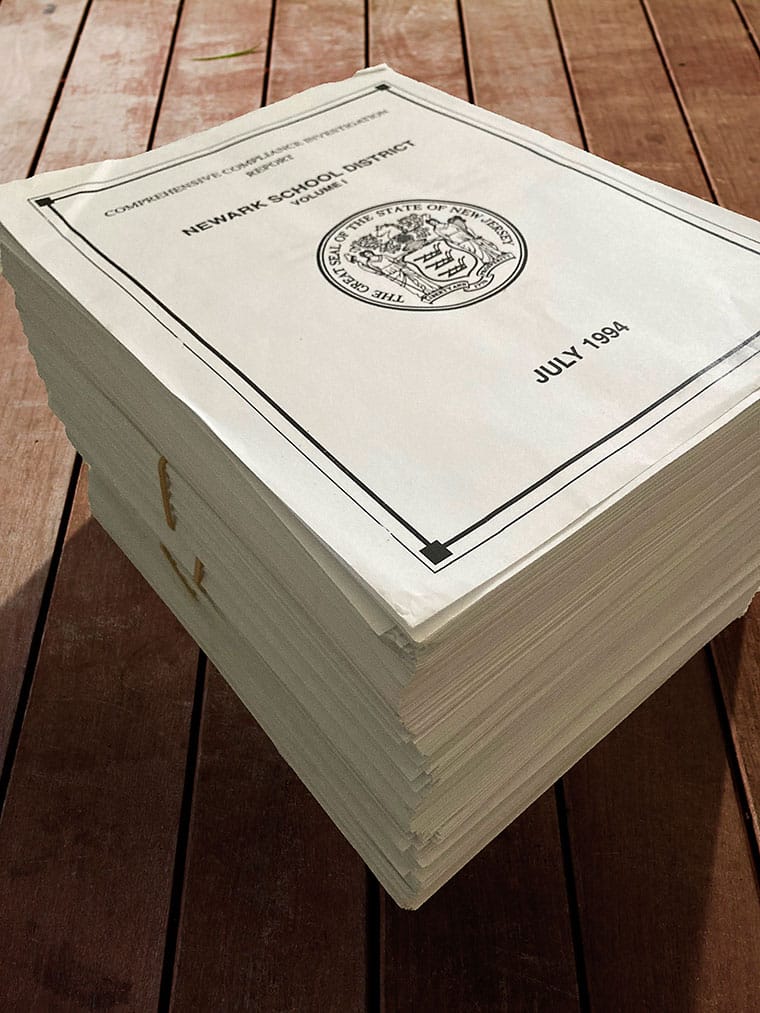

District opposition notwithstanding, the report was released the following summer.

It was well over a thousand pages long …

… and contained findings …

… that shocked the public.

Academic achievement levels were appalling.

School facilities were in a state of disaster.

Appropriate instructional materials were nowhere to be found.

Instruction was plainly inadequate.

And through it all, central district staff showed a complete disregard for the intolerable conditions they were responsible for.

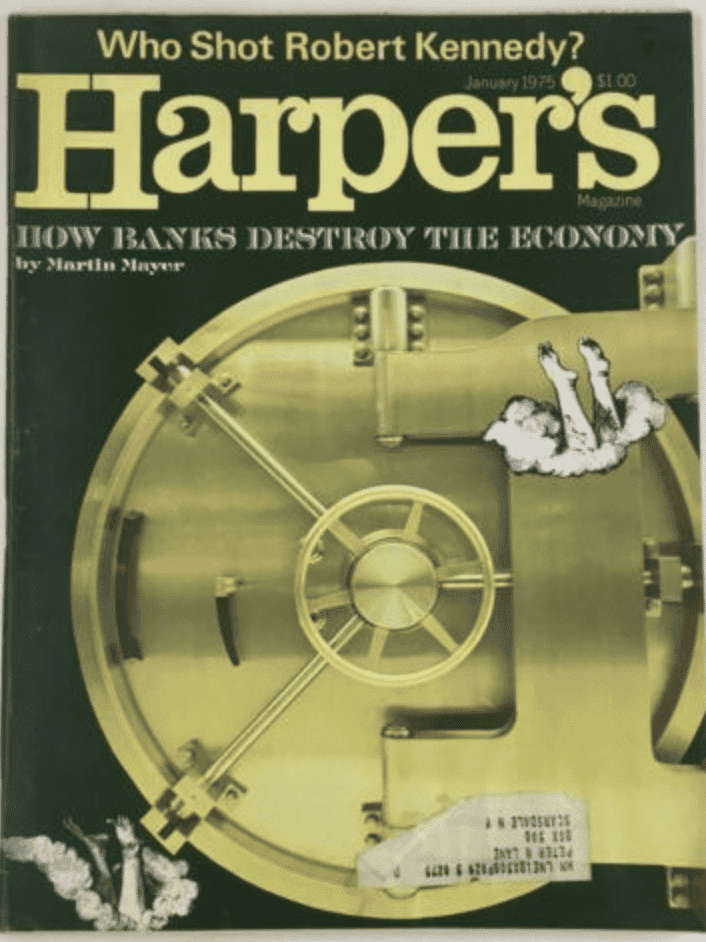

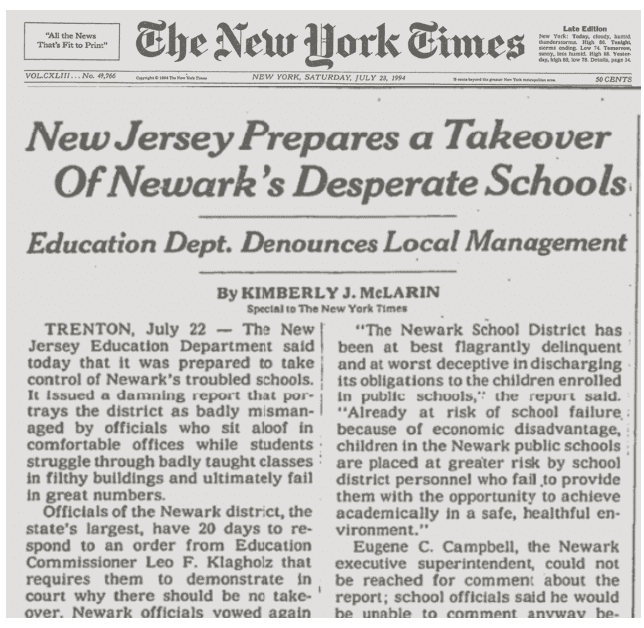

It led to the state preparing to replace the elected school board, remove the superintendent and other top district leaders, and undertake direct management of the school system from a state level.

Predictably, the school district fought hard against the proposed takeover, taking its case to court.

Ultimately the state prevailed, but not without having to have the district’s prior leadership physically escorted from their offices.

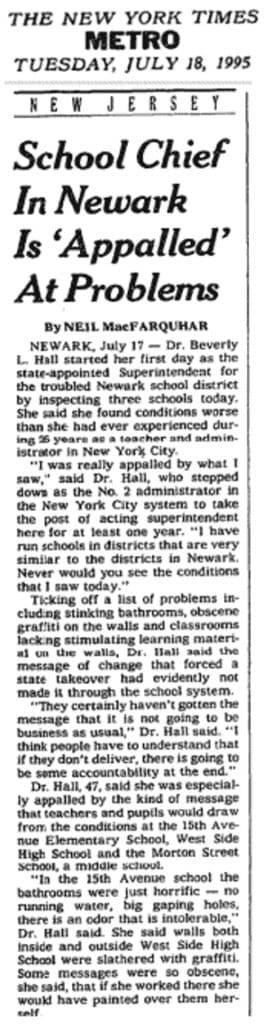

Three days later, Beverly Hall, the state’s appointed superintendent for Newark spent her first day touring the district. What she saw shook her.

Dr. Beverly L. Hall started her first day as the state-appointed Superintendent for the troubled Newark school district by inspecting three schools today. She said she found conditions worse than she had ever experienced during 25 years as a teacher and administrator in New York City.

I was really appalled by what I saw, said Dr. Hall, who stepped down as the No. 2 administrator in the New York City system to take the post of acting superintendent here for at least one year. I have run schools in districts that are very similar to the districts in Newark. Never would you see the conditions that I saw today.

In his authoritative history of Newark, Robert Curvin dedicated an entire chapter to describing the state of public education in the city in the 80s and early 90s.

The title he chose for that chapter said it all: “Pity the Children“

Against this backdrop of decades-long dysfunction and brokenness in Newark Public Schools, a new reform movement in public education was beginning to take root in other parts of the country.

In 1991, Minnesota passed the nation’s first charter school law.

The following year, California followed suit.

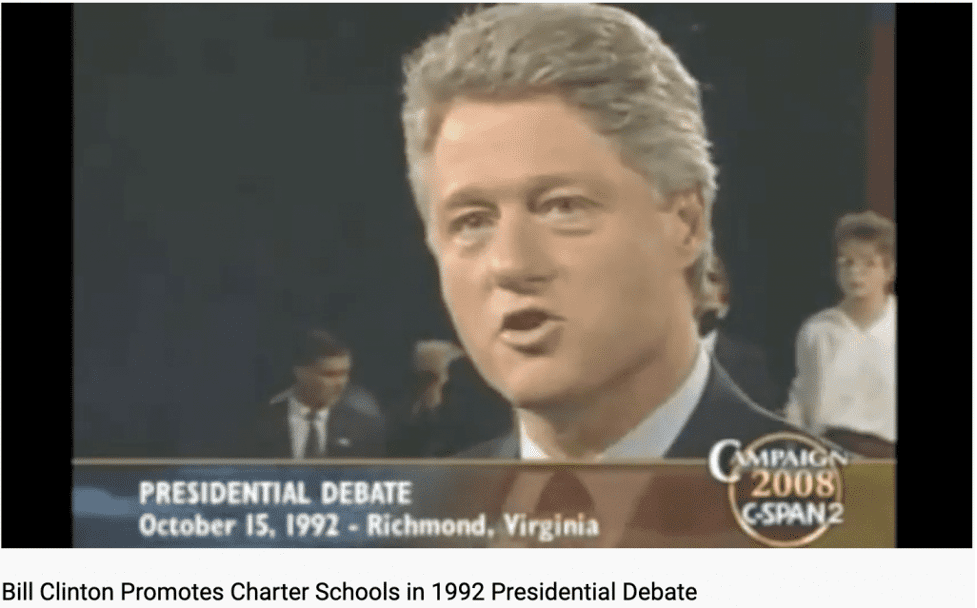

That autumn, Bill Clinton began publicly championing the chartering concept on the presidential campaign trail.

Soon efforts to pass charter school laws were spreading across the nation …

… including in New Jersey.

The stage was set for a policy breakthrough with the potential to bring a level of transformation to Newark schools unlike any the city had seen before.