Newark Chapter 6: Reforms are Met With Pushback and a New Book Rushes to Judgement

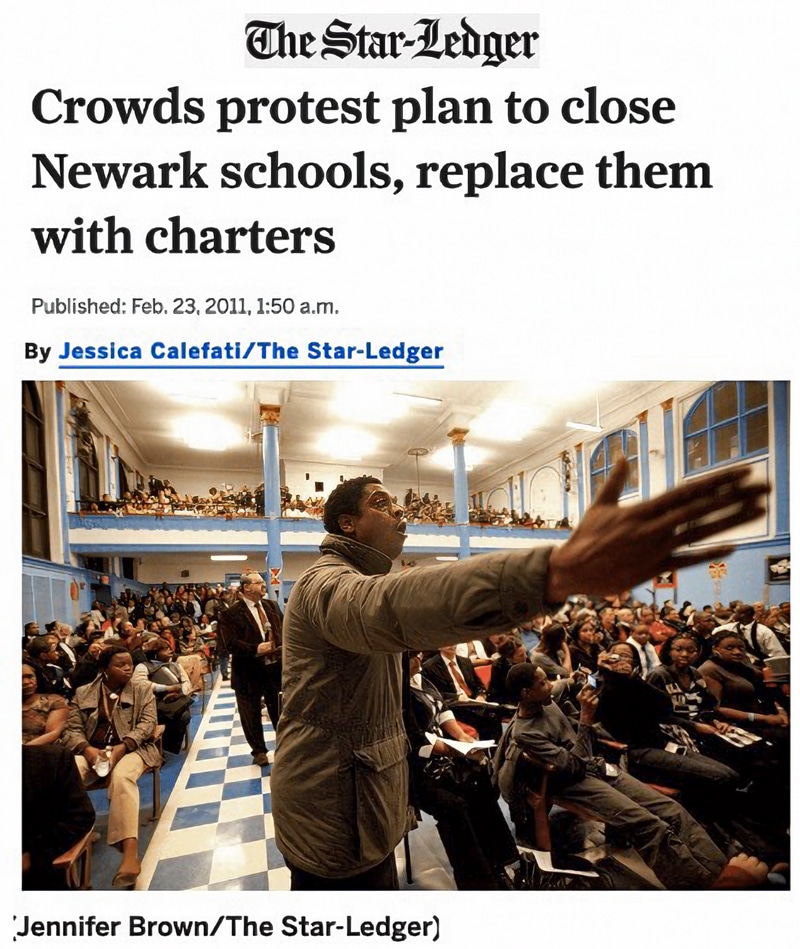

Even before Cami Anderson was appointed Superintendent, it was clear that a big part of the overall strategy for improving Newark Public Schools would hinge on closing underperforming district schools and consolidating under-enrolled ones to create space for new charter schools to open. Early in 2011, less than six months after the Zuckerberg gift announcement, a plan for consolidating campuses went public …

… sparking an immediate backlash …

… where many community stakeholders, including reform-friendly Newark Public School Advisory Board Members, objected to a plan that had been formulated with little transparency and community engagement. Many also objected to the fact that the plan had been crafted by highly compensated consultants who did not reside within Newark. Ultimately, in the weeks before Anderson’s hiring, Cerf and others at a state level overruled the Newark Public School Advisory Board and approved the creation of six new high schools.

All through Anderson’s first year as Superintendent, it was clear that the closure of underperforming district schools would continue to feature prominently in reform plans. Again, the teachers union and others claimed that they had been left out of the process …

… resulting in new rounds of protest being staged at Newark Public School Advisory Board meetings.

In the early going, Anderson and Del Grosso managed to keep their relationship cordial enough that they were able to complete negotiations for the new teacher contract. But by the early months of 2013, their relationship began to completely unravel. Much of it originated from the fact that a contingent of Del Grosso’s members became more vocal in their criticism of the union president’s support for the new contract.

By spring, their numbers had swelled to be large enough to narrowly miss ousting Del Grosso from his position of leadership.

That summer, relations had degraded to such a point that Del Grosso refused to sign the district’s Race to the Top grant application …

… effectively disqualifying the district from receiving tens of millions of dollars for improved classroom technology and professional development.

It set the stage in December of 2013 for the greatest controversy of all – the release of Anderson’s “One Newark” plan …

… wherein her team articulated its vision for moving the district to a new paradigm altogether, one where a host of schools would be closed and consolidated and where a wide range of new options, some operated by charter schools, others by the district, would enable families to choose schools through a common application and enrollment platform that would be open to all.

It was a grand vision, but detail was lacking, and many of the plan’s changes the teacher union and others found threatening.

In the early months of 2014, the blowback against school reform in Newark reached its crescendo with several public hearings descending into utter chaos. In one, Del Grosso called for Anderson’s termination, referring to her as “the most conflicted superintendent in the history of New Jersey.”

In others, the vitriol directed against Anderson devolved into highly personal attacks …

… that led Anderson to begin foregoing many public meetings altogether. Soon she moved her family outside of Newark citing safety concerns.

That May, exactly three years and one week since Anderson’s hiring, and just over three and a half years since the Zuckerberg gift announcement, the New Yorker published an article entitled “Schooled.”

The article’s author, long-time education reporter Dale Russakoff, did not dispute the desperate need for improved public education in Newark, citing decades of district mismanagement, malfeasance and plain incompetence. But she argued that the reformers had gone about their work in a highly ineffective, top-down fashion that failed to engage communities authentically and that relied too heavily on highly compensated consultants from outside Newark. In her article’s rendering, not only were the progenitors of Newark’s reform efforts having their comeuppance, but so too were school reformers across the country writ large, people who Russakoff believed to be infused with hubristic tendencies comparable to those brought to Newark by a governor, a billionaire, a media tycoon and a US senator-to-be.

The implication was clear:

Not only had a small number of extremely powerful ed reformers been schooled in Newark. So too had an entire generation of ed reformers working in many places across the United States.

Five days after the publication of the article, Ras Baraka, Newark’s recently elected new Mayor, a figure who was among the very few public officials to have opposed the Zuckerberg gift from the very beginning …

… joined the Newark Teacher Union and various community groups in calling for the return of local control to the district.

Within days, the national press was rife …

… with accounts …

… of the failed reform efforts in Newark.

Even before the publishing of the New Yorker article, the unusual political coalition holding together reform in Newark had begun to erode.

Booker was elected to the US Senate.

The governor became engulfed in other controversies.

Cerf soon stepped down from his role as New Jersey Education Commissioner.

Not long after, Anderson was gone as well.

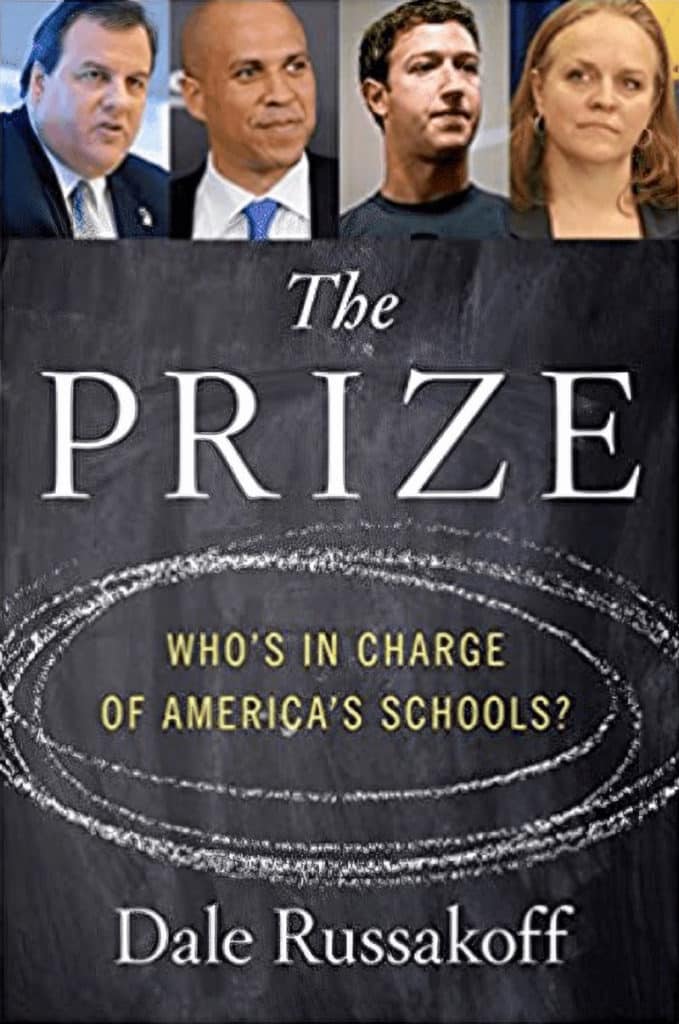

Three months after her departure, Russakoff published a book elaborating on the central thesis she advanced in her New Yorker article.

Only now her criticism became even more pointed, drawing attention to the subject of who controls public education in the United States.

Indeed, the book presents a picture of “the prize” of public education being control itself, a reality that sadly becomes the focal point in many contexts where bold reform is attempted, not the merits of the reforms themselves, nor who might benefit from them, but who is ultimately in charge of them. And, equally as sadly, we often fail to recognize that “the prize” – the control of public education – is not some shiny object that can only be reached for and won anew, but is in fact something that has been firmly secured previously by existing forces who resist its loss with the all the gusto, if not more, than any new entrant who might grasp for it, or who might genuinely seek to re-situate it altogether where many think it most rightfully belongs: in the hands of parents and educators empowered to act with all the agency that should be their right but which they so sorely lack given the tragic misdesign of our country’s public education system.

Certainly, for the few years that The Prize focuses on, the gladiator-esque quest for control of Newark’s public schools often became the central focal point of effort and discussion. But looked at within the context of this exhibit, one that takes a multi-decade perspective, rather than just a multi-year perspective, the period covered in The Prize appears but a brief episode against a much broader drama of profound change and improvement.

It is the quest for that much more profound prize, a quest that continued unabated through the years portrayed in Russakoff’s book, that we now return our attention to.